Northwest Coast Carver Ellen Neel Breaks Tradition

The Story of Canada’s First Female Totem Pole Carver

Dave: When I came across this book online, it immediately caught my attention. So, I reached to Figure One Publishing for a review copy. I wanted to learn more about some of these women carvers and possibly interview a few for this site. Well, the book already contained an extensive interview about the late Ellen Neel. Figure One was kind enough to share that excerpt. Here it is!

Excerpt from Curve!: Mary Anne Barkhouse on Ellen Neel

Interview by Curtis Collins

Mary Anne Barkhouse (Kwakwaka’wakw; b. 1961) studied at the Ontario College of Art and Design University in Toronto and currently resides in southeastern Ontario. Barkhouse has been a practicing artist for over thirty years and has exhibited her work in venues across Canada.

Ellen Neel (Kwakwaka’wakw; 1916–1966) was Barkhouse’s great aunt. An artist from Alert Bay, BC, Neel became the first woman in Canada recognized for carving totem poles professionally and was niece to renowned artist Mungo Martin.

The following is lightly edited from a recording of a conversation that took place on November 23, 2023, via videoconference. This article is a condensed version of the original.

Curtis Collins: Ellen Neel’s artistic production was shaped by her circumstances in Vancouver; can you please describe the household?

Mary Anne Barkhouse: As I understand it, Ellen’s husband, Ted Sr., had a workplace accident and seriously injured his back and couldn’t work for a time. So then the question becomes, how do they support themselves when there’s not much of a social safety net in the 1940s and 1950s? My grandmother and Ellen had both been taught about carving and design by Charlie James. My grandfather Fred Cook said when he and my grandmother were first married, she carved a bit and would sell these small carvings when the steamship came to Alert Bay, which would have been about once a week. With both sisters having that background of being taught by their grandfather, it seems that carving was a way to make some extra money from a young age, so perhaps it would follow that later on it would be a natural to develop that as a full-time business.

By the time that my mother went to live with them she said that her Uncle Ted would prepare the wood, cutting it down to size with a chainsaw, in a workshop in the basement of their place in East Van. And as the boys got older, they would help out in the studio as well.

Mom and her cousin Dave [David Neel Jr.’s father] both went to Britannia High School, and she remembers that he used to go by tram to art school in an old library on Main and Hastings on Saturday morning. She describes him as an amazing artist and he had his paintings up in the hallways at school . . . he even helped her do a project for her art class, which she got a good mark on.

When my Mom went to live with them, Auntie tried to teach Mom how to do a few things, but eventually Mom ended up just painting the ears of the Thunderbirds on the small poles, and even that, by her own admission, she “mucked up,” so Auntie gave up trying to teach her anymore. My mother’s talents lay in other fields!

All of these recollections of life with the Neels that my Mom has told me have contributed to this sensibility about art-making that I have grown up with and that was reinforced by long conversations I used to have over bottomless cups of coffee with her son, Bobby Neel, back in the ’80s. As well as carving, Bobby worked a lot in silver, producing beautiful jewellery. This inspired me to take up metalsmithing, as well as sculpture, when I later went to art college in Toronto. The idea of making artwork for different purposes, and that it was a completely valid and perfectly fine way of doing things.

CC: There was a well-defined commercial orientation to Ellen Neel’s work. How do you contextualize such a quality?

MAB: Ellen had a knack for not only the design aspect but the business side as well, which is somewhat unique I think, because a lot of artists will be good at one and not the other. Just because you have a passion for the design and the making of things doesn’t necessarily extend to having a passion or a talent for the business aspects.

From what I understand from my conversations with my mom, as well as reading newspaper articles about Ellen from back in the ’60s, Ellen was very active in promoting understanding and appreciation of Northwest Coast art by presenting to community groups and giving talks at universities. I suppose in today’s lingo it might be called “growing your brand.” Something like that takes a lot of energy and courage at any time, especially in the era she was doing it . . . not to mention that she was a woman, to boot.

So, I see all of these efforts naturally manifesting themselves in many of her works being created for sale, not ceremony, and that also goes back to what she and my grandmother learned from Charlie James. Especially at this political moment that we find ourselves in, these distinctions are important, and it is yet another thing that I’ve carried with me as a direct result of conversations with family—there are aspects of our culture that we keep for ourselves, and then there are other parts shared with the world at large.

Ellen supported herself and family from a variety of sources, as I understand it. She created her own business opportunities, such as the shop at Stanley Park, in addition to the sales to a network of other stores and galleries across the country, as well as becoming involved with what I see as groundbreaking initiatives like the Totemland series.

CC: The focus of this exhibition is on carving; however, I understand that carving was just one among many artistic practices in the Neel household.

MAB: I guess my grandmother and Ellen thought that Mom needed to be occupied when she wasn’t doing her nursing studies, otherwise maybe she’d get into trouble? As if studying full-time for a nursing degree wasn’t enough work! But both my grandmother and her sister were nothing if not hard-working ladies, so perhaps it follows that they would impress that upon the next generation.

In any case, my mom had these embroidery projects she was expected to complete. My grandmother would prepare long swatches of this beautiful cotton, cut to the size of a table runner or decorative cover for a set of dresser drawers. Ellen would then draw a design on it, and this was what Mom was supposed to embroider during all her “free time.” We still have them . . . they’re behind me in the drawers right now. And my grandmother would do a crocheted edging to finish it off nicely and voila . . . a beautiful table covering.

CC: This exhibition features a selection of masks and small poles rooted in Kwakwaka’wakw ceremonial and heraldic forms that Neel transformed for the tourist market. Can you comment on this aspect of her practice?

MAB: I think that she investigated various forms amazingly well in order to make that transformation from ceremonial-inspired to commercial object. Just looking at the selection you have here are some good examples—from very small tourist items and then some larger, more involved ceremonial-type works. Although, the various burnt-wood Dzunukwa [“Wild Woman of the Woods,” also known as Tsonokwa] and Wind masks would have been made for display purposes as opposed to ceremonial use, as is evident from their lack of holes for the eyes, which goes back to the whole idea of “intended purpose” that a lot of carvers today still address. There are pieces used in ceremonial settings and they have regular use. And then there’s other ones that are made as commercial items only; it’s a part of the decision-making process for any artist.

CC: What are the strengths of how Ellen Neel developed small-scale works?

MAB: In terms of the pieces that are created for different purposes—just because the totems are small doesn’t mean that they took any less care. There’re some really interesting design decisions that she’s made to shrink to that scale. The manner in which she was able to condense Kwakwaka’wakw pole-based forms is genius. It’s one thing to expand something, but it’s a special skill to condense it so precisely and beautifully in these miniature poles. Which is why I’m so sad that I broke this little one [Barkhouse holds a tiny totem to the camera]. In my defense, I would have been like five years old at the time [laughs].

CC: Who taught Ellen how to carve?

MAB: Ellen was taught to carve by Charlie James who was, as mentioned, her maternal grandfather. I don’t know if her uncle Mungo Martin had any role in teaching her. I’d have to clarify that. Although, I do have a photograph of Charlie carving with a couple little girls, two or three little girls, sitting beside him. One of those girls would be Ellen and one would be my grandmother. So, I am assuming she became interested in carving as a child and obviously it was something that she was very adept at and must have loved to do. But like any artist, when you’re working at two o’clock in the morning, you’re probably telling yourself, “And I’m doing this because . . . why?”

CC: What were some of Ellen’s most innovative business ventures?

MAB: Most definitely the Totemland initiative that she entered into with, I think, either a tourism or historical society in Vancouver, is one instance of that innovation. And it’s a great example of a purpose-driven artistic form that Ellen developed. More specifically the miniature poles with a globe-like form on the bottom featuring a green and blue depiction of the BC coastline. If you’re considering unique styles or unique commercial partnerships and endeavours, Ellen stands out as exceptional in her time. I don’t know of too many other Indigenous artists that have done anything like the Totemland series, which extended from carving to the custom bone china Totem Ware she designed in partnership with Royal Albert China.

CC: How did Ellen Neel communicate the importance of the art tradition she was part of?

MAB: She did a lot of public lectures in Vancouver. Mum was saying that she used to know when Auntie Ellen was going out to give a talk because she had a certain orange dress that she liked to wear. In Phil Nuytten’s book there is a reference to a lecture that Ellen gave in 1948 at UBC that is as poignant today as it was back then.1 She was one of the Indigenous artists on the coast, along with Mungo Martin, that were very vocal about the tenacity of the art form, about the vibrancy, about its contemporary relevance. And it’s important to remember that she was a young woman talking about Kwakwaka’wakw cultural traditions that were still technically outlawed by the Canadian government at that time (the Potlach ban section of the federal Indian Act was in place from 1885 to 1951). And it may be pertinent to remember that just because something is banned doesn’t necessarily mean that it disappears entirely . . . but it does force things to go underground, as it has in so many instances throughout history.

CC: What do you think is Ellen Neel’s artistic legacy?

MAB: Ellen always left the door open to the advancement of traditional forms. She used her understanding of the Kwakwaka’wakw carving style and interpreted everything in her own way and made it contemporary. So, the artists after her—not just people in the family, like myself; and there’s many other artists in the family as you know—but artists at large, especially women artists on the coast, are indebted to Ellen Neel. It’s like she was saying, “This is something you can do!” Unfortunately, it has taken the Canadian art scene at large sixty years to catch up to what she was advocating.

Which is not to say that she didn’t have respect for her practice in certain circles at the time . . . but there were other ways in which she wasn’t respected. For example, she applied to [the] Canada Council for the Arts for funding, but to no avail. We have come a long way from those times when a very well-respected professional artist like Ellen would be turned down by [the] Council as there wasn’t the recognition for Indigenous arts that there is today.

CC: The commercial or tourist orientation of Ellen Neel’s miniature poles and display masks is often cited as diminishing their artistic value. What do you think of such a criticism?

MAB: I think that’s a ridiculous criticism, because a lot of work by artists from time immemorial is directly linked to patronage of some kind. Just think of painters from the past hundreds of years—from Nicolas Poussin to Van Gogh, Renoir, Monet or Picasso . . . they were all painting to sell. Some, like Poussin, had the French kings and the Medicis as patrons; the others had networks of art dealers. But is that same criticism even part of the conversation about such Western art icons? So, I just wonder, is that because she was a woman? Is that because she was Native? Is it because of both that they minimize her work due to its commercial value? Because if you look at other art forms in cultures around the world, that commercial value may have existed too. But mostly I’m thinking of European precedents. That same magnifying glass isn’t applied to the origins of those people’s work. So that’s a very valid point about the devaluation of Ellen’s art that you have raised. I might not be here if it weren’t for Ellen convincing my grandmother to send Mom to high school in Vancouver. I would not have grown up with that influence of art as being part of a respected profession.

When I attended art college, I remember the families of some of my fellow students withdrew support from them, as art was not valued as a way to make a living. Thanks to Ellen, however, my parents viewed a career in the arts differently. Ellen, and Mungo and Charlie before her, effectively created the template for how one can make a perfectly reasonable living through the arts and, in so doing, create a voice for expression and dialogue for community. It set that precedent of design, respect, education, and outreach that I try to be mindful of every day.

CC: Do you have any closing thoughts on the grouping of women carvers, starting with Ellen Neel in the 1950s and continuing to the present day, that are part of this exhibition?

MAB: I think that an exhibition like this is important and long past due. I’m sure that there have been other examinations of art by women over the past few decades. But this exhibition comes at a pivotal time, when some of the Indigenous knowledge keepers are leaving us. It’s really important to try to document that cultural lineage, and to connect the dots with these intergenerational influences, the why’s and how’s of art production, as well as to capture the anecdotes of these women’s lives. It all serves to tell this larger narrative of perseverance, creativity . . . and good humour.

CC: Thank you for sharing your family history.

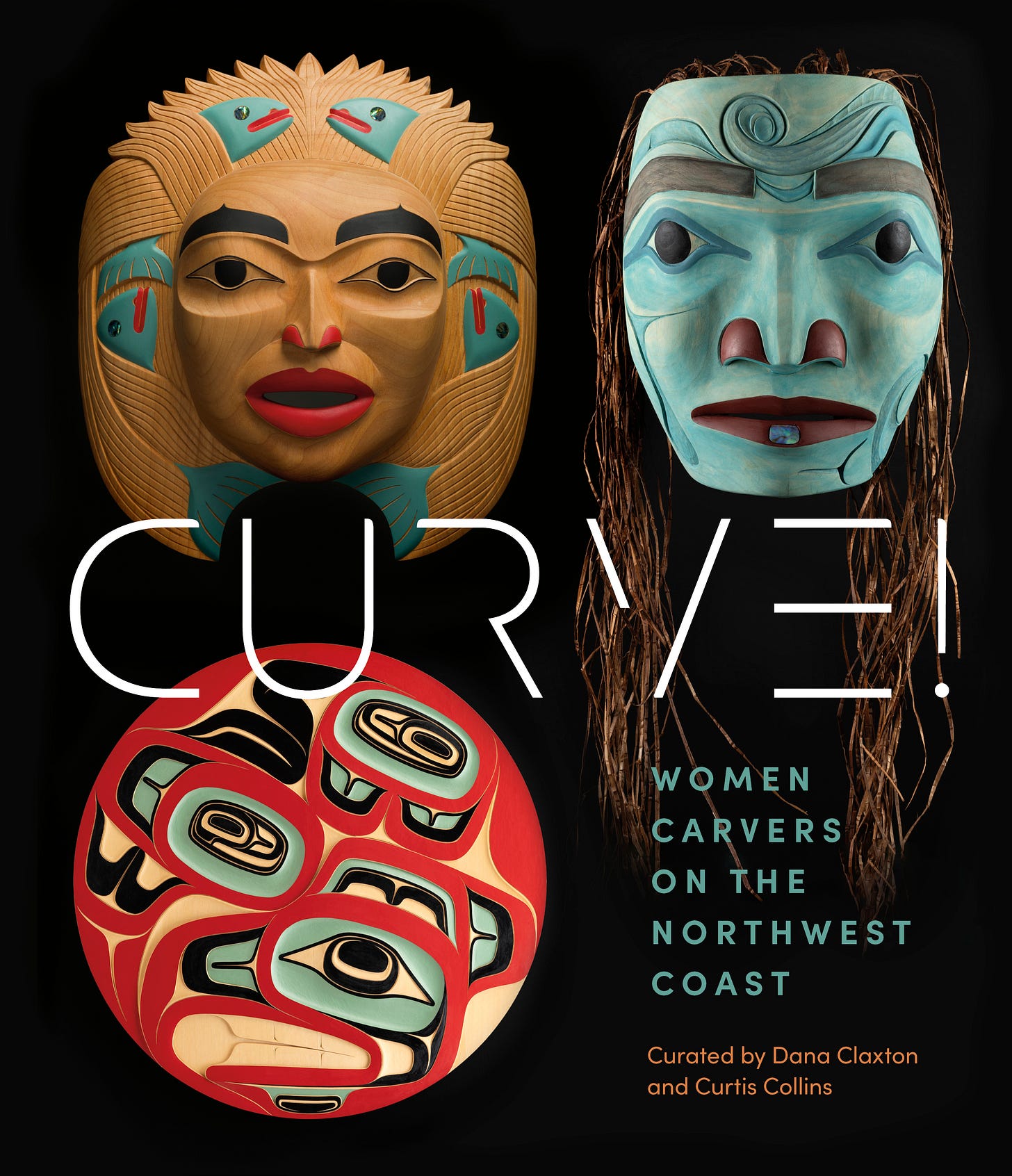

Excerpted from Curve! Women Carvers on the Northwest Coast. Curated by Dana Claxton and Curtis Collins. Copyright © 2024 by Audain Art Museum. Excerpted with permission from Figure 1 Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.