Springing the Trap: The Tale of the Flying Dutchman

How the criminal career of a notorious northwest coast pirate came to an abrupt end.

Midnight March 3, 1913

Stooped in the coved entryway of the Fraser and Bishop General Store in Union Bay, a man yanks a skeleton key from his pocket. He gropes for the door’s lock and shoves the key in. The door groans open. Cloaked in midnight’s shadows, he and a second man slink inside, their footfalls deadened by soft-soled shoes. Once more, the man sinks a hand deep into the pocket of his Mackinaw coat. With a wink of his electric flashlight, he exposes the unguarded loot.

But before the men can stuff their sacks, a lock jiggles at the store’s second entrance and the two freeze. The first man again thrusts a hand into his coat. This time he wrenches out a .44 calibre Colt revolver. Their hearts thump. They crouch between counters filled with dried goods and breathe air choked with spices and sweat. The man aims the Colt at the second entrance.

***

What happened next? For over a century, various writers have recounted the story of one of Vancouver Island’s most infamous shootouts. From the first time I read about the notorious pirate and smuggler nicknamed the Flying Dutchman and his exploits in Union Bay, I wanted to write my own version of the tale. I began my research by scouring the handful of published versions out there. But I noticed inconsistencies between them. Unsure of which ones to believe, I quested for the truth. The source documents I unearthed from both Canadian and American archives, prison records, and newspapers not only illuminated the small details but also called into question whether the gunman deserved his final judgment: execution.

***

In 1870, over forty years before the general store robbery at Union Bay, one of Louisiana’s newest residents was a squalling baby named Henry Ferguson Sastro. The baby looked up at his German-born parents through steel-grey eyes. Other distinguishing features included a mole on his right cheek and bow legs that never straightened out. In 1882, his father died, followed six years later by his mother. Eighteen years old and parentless, Sastro possessed a face that looked as if it could take a punch. Standing 173 centimetres (5 feet 8 inches) tall and weighing in at eighty-two kilograms (180 pounds) of muscle and bone, no doubt he could deliver punches too. At some point he joined the U.S. Merchant Marines, a civilian organization responsible for international and domestic seaborne trade. Here he became steeped in the life of a seaman.

***

A decade before the robbery, on October 18, 1901, two police officers scrambled from their boat at a Whidbey Island dock in Puget Sound. The officers rushed a nearby cabin and flung the door open, guns drawn. Inside, Sastro and another man raised their hands. The officers charged Sastro with the theft of thirty-five sacks of oats from a warehouse a year earlier. Long since a Scotsman’s breakfast, the oats were a minor, easy-to-prove offence. In court two months later, Sastro admitted to a more wicked crime: smuggling nine thousand pounds of opium from Canada to the United States over a number of years. The judge sentenced him to fourteen years of hard labour at Walla Walla State Penitentiary.

The penitentiary was a prisoner-run, self-contained city that produced goods for sale—like grain sacks for oats. Inside, Sastro met the man who would eventually become the number one witness in his murder trial. In 1903, William Julian got three years hard time for grand larceny. Of Welsh heritage, Julian was born in the same era as Sastro. His lustrous black hair sat atop a baby face with a Celtic complexion. In contrast to Sastro the slender man stood at 5 feet 3 inches and weighed 135 pounds.

Sastro was released in 1908 for good behaviour, but that behaviour failed to extend beyond incarceration. In 1909, a “Wanted” poster pegged Henry Ferguson (by now he had dropped Sastro from his name) as the prime suspect in a post office robbery in Washington State. He and two other men had snuck in at night and stolen $176.80. A self-taught locksmith, Ferguson gained entry with a skeleton key and worked a safe. Police captured the other two culprits, but “Water Pirate Henry Ferguson, alias ‘Jack the Flying Dutchman,’” escaped. The alias Flying Dutchman comes from sailors’ tales of a ghost ship that has haunted the seas for centuries. Sighting the ship foretells doom. The people of North America’s Pacific Coast affixed the name to Ferguson somewhere along his travels.

The poster explained that he “wears a black cap when in boat and a light-coloured canvas hat when on shore” and “is generally armed with a Colt .44 revolver and a double-barreled shotgun.” Known to be handy and clever, Ferguson would sometimes repaint and refit the cabin on his 16-foot boat, the Spray. With a three-horsepower gasoline engine and small sail, the Spray was quick and nimble.

The poster referenced Ferguson, William Julian, and a woman of mixed Indigenous ancestry, “all of whom are supposed to be in Nanaimo, BC, or vicinity, as their plan was to rob a company store at that place. Both of these men are desperate characters, and I am informed left here about a week ago for B.C. for the purpose of murdering two men and committing a robbery.” The poster said that “Ferguson is well posted in the B.C. waters and on Puget Sound. He talks about Yulu Island, Frazer River, and Bring Berge Island” (a misspelling and likely reference to Lulu Island—one of the seventeen islands that make up modern-day Richmond—the Fraser River, and Bainbridge Island, west of Seattle). For the Washington authorities, his capture was “of the utmost importance on account of the crimes he has committed and for those he threatens to commit.”

This heat is perhaps what drove Ferguson and Julian into Canada, where U.S. law enforcement could not follow. But BC was no safe haven. They had jumped from a sinking ship into a heaving sea. Their Wanted poster trailed the pirates north into Canada, where a man hardened by decades of policing on the coast readied himself.

***

Chief Constable David Stephenson began his job in 1881 as the Island’s lone BC Provincial Police officer, stationed north of Esquimalt. Before immigrating to Canada, he had been a member of Queen Victoria’s Guard of Honour. He looked every part the Canadian frontier cop—a smart uniform, stabbing glare, and thick, drooping moustache on an otherwise clean-shaven face. In the early days, he travelled the coast alone by canoe to take prisoners to court in Nanaimo. Whether they helped paddle is unknown.

In the years after the Wanted poster’s publication, pirates marauded the BC coast, committing a string of burglaries. On October 12, 1912, the Daily Colonist reported that thieves blew a safe in Victoria and made away with nearly six hundred dollars. Vancouver saw safe-breaking attempts in the same month. On December 15, burglars broke into the safe at Nanaimo City Hall. Up Island in Union Bay, around the same time, a woman named Mrs. Bishop was working in a hotel kitchen. She heard a noise and went down the hall to investigate. According to The Friendly Port, a book about Union Bay’s history, a burglar was breaking in and heard her coming. The burglar ducked into a bedroom and hid in a wardrobe. She never did find him, but “Mrs. Bishop’s brother was up staying, and he had an old pair of comfortable pants. One day he went to put them on, and they weren’t there.” Police found the pants months later at the Flying Dutchman’s hideout.

With an area eight times larger than Puget Sound under his care and few officers to help him, Stephenson had found it impossible to apprehend the culprits. He needed a break in the case. Convinced the pirates would hit Union Bay again soon, he planned a trap. For this he enlisted two undercover officers. The first, Gordon Ross, had fought in the South African war as a Lovat Scout. The Scottish sniper regiment was famous for being a pioneer of the ghillie suit, a type of camouflage that helped wearers blend in with their background. The second, Harry Westaway, hailed from PEI. Up until his thirtieth birthday he lived with his parents. According to the census, he worked as a painter before becoming an officer. Stephenson posted the two men in Union Bay at the beginning of February 1913.

***

On March 3, 1913, the Farmers Institute on Lasqueti Island was holding a meeting. Two reputable Lasqueti community members, Henry Wagner and William Julian, told their neighbour in Scottie Bay they were leaving to attend the meeting. At four in the afternoon, Wagner’s wife and children watched them motor out of the bay. The next time they saw Wagner, he would be behind bars.

The Flying Dutchman’s true name depended on who you asked and where you asked them. The desperado’s actions necessitated aliases to elude the authorities. In Washington State, he answered to Henry Ferguson Sastro and Henry Ferguson; on the Canadian side of the line, Henry Wagner.

With his three-horsepower engine, Wagner could travel a little faster than a horse could walk. He never intended to make the Farmers Institute meeting. From Scottie Bay, the most direct route to Union Bay led him west to Hornby Island. Here, he hooked slightly south around Denman Island. One of the few nighttime guides, the blinking Chrome Island lighthouse, lay to starboard just offshore from Denman’s southern end. Darkness shrouded the headlands and shoals as they sputtered northwards.

During Wagner and Julian’s northbound journey up Baynes Sound, Constables Gordon Ross and Harry Westaway played cards and drank beers in the Nelson Hotel. As the port for the Cumberland coal mines, Union Bay’s long wharf welcomed ships from all over the world. A short stroll away, the hotel faced the sea. Its bar was a fine place to spend the evenings, drinking and chatting to travellers. Ross and Westaway had waited for a month, night in and night out, for criminals to appear at the Fraser and Bishop General Store next door. At night, the white building, with its high false front, sat dark and quiet.

At midnight, the officers noticed a light. They walked into the post office adjoining the store to investigate. Once inside, they heard a creak in the store proper, as if someone had stepped on a floorboard. Westaway clutched a pistol. Ross gripped a flashlight and baton. Unknown to them, Wagner was peering down the sights of his Colt .44.

***

Union Bay’s local police officer was on duty not far away at the colliery dock when he heard someone yelling for help. At the store’s entryway, the door’s shattered glass crunched under his feet. A shadow beckoned him inside. The officer clicked on his flashlight to behold Gordon Ross standing by the door. Beyond him waited a grisly sight—a captive lay unconscious on the floor, bloodied and beaten to a pulp, and Harry Westaway lay dead in a pool of blood.

Chief Constable David Stephenson happened to be in Cumberland that night, visiting another constable, his son, Albert. They received a call about an incident in Union Bay. A bumpy thirty-minute drive down Royston Road and what is now the Island Highway and the two officers arrived on the scene. Someone poured cold water onto the prisoner. Stephenson identified the barely conscious man as the Flying Dutchman.

Wagner was brought to the Cumberland lockup, where he asked to have a reporter sent to take down his story. He planned to sell the story and give the money to his wife. Permission was not granted.

On March 13, 1913, an officer named George Hannay shepherded Wagner to the Nanaimo Gaol. George Hannay and the entire force had had a busy March. They had scoured the area for an unidentified second man who had escaped from the scene of the burglary. After the botched burglary, Julian had taken the Spray’s skiff and started rowing the thirty miles back to Lasqueti Island. On March 7, with two aching arms from three days of rowing, Julian arrived on land, only to find Hannay waiting for him, pistol drawn. Perhaps it was Wagner who told police where to find him.

***

Proceedings in Wagner’s trial began on May 13 at Nanaimo’s courthouse. The doctor who arrived on scene early in the morning after the murder testified that Westaway had died from a gunshot wound through his right lung, but was unsure from which direction the bullet had entered. A bullet’s exit wound is typically much larger than the entry wound. However, Westaway’s two deadly holes measured about the same. As well, the doctor found two gashes about two inches long on the top of Westaway’s head. He also noted how Wagner had taken a thrashing while Ross had no marks on him.

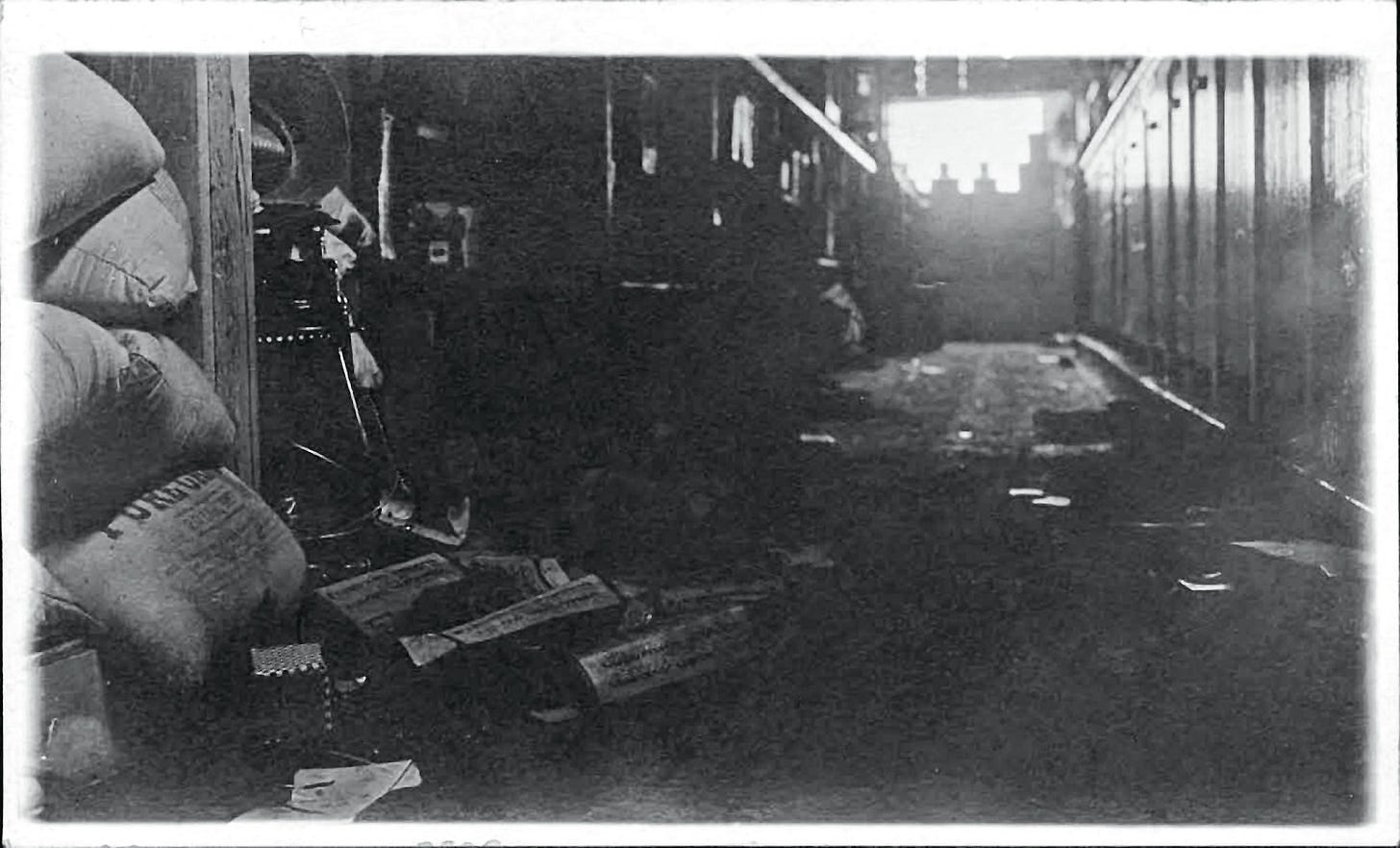

Gordon Ross came to the stand next. His testimony went like this: He and Westaway entered the post office and heard the creaking floorboard in the store. Ross pointed his flashlight into the store but saw nothing until he directed the beam to his left, where he found himself looking down the barrel of Wagner’s Colt .44. Wagner was crouched on one knee in a narrow corridor between the counters. Ross killed his light and rushed him. Wagner fired. The bullets missed Ross in this narrow corridor and hit Westaway, who was behind him. Westaway said, “I’m shot, Gordon, do you have him?” While Westaway bled out on the floor, Ross and Wagner fought for the gun, knocking supplies off the shelves. The crime scene photos show disarray. Eventually, Ross subdued Wagner, knocked him unconscious, and handcuffed him. Ross admitted during questioning to being punched several times by Wagner.

As the doctor noted, however, Ross was unscathed. He did not even have marks on his knuckles. Victor Harrison, the lawyer assigned to Wagner, raised this anomaly during cross-examination: “What was he fighting,” Harrison asked Ross, “the counter or walls? What was he fighting? You are not marked up. I don’t understand you.” Ross responded, “I don’t understand it myself.” Harrison asked Ross if he’d had anything to drink that evening. Ross sketchily admitted he’d spent the entire evening in the hotel bar but that he’d drunk only one beer. Post-trial, Harrison stated in a document that he sent to Ottawa to have the case appealed that Ross was a known drunk.

Another question raised by Harrison was how the bullet had missed Ross in the narrow corridor and hit Westaway, who was behind him. Ross did not know.

Wagner’s testimony contrasted with Ross’s. He claimed a drunken Ross had accidently shot Westaway while Wagner and Westaway wrestled. This version of events might explain why Westaway had two gashes on his head and Ross was unmarked, and it would also solve the bullet wound puzzle. A bullet entering from the back would add some credence to Wagner’s version.

The prosecutor asked Wagner about his past crimes. Was it true he’d been a member of Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch, the infamous American train-robbing gang? Wagner answered no.

Next, Julian came onto the stand. His story was short and simple. He entered the store behind Wagner, clutching his coattails in the dark. When a light flashed on them, Julian fled, and as he exited the store, he heard two gunshots. If true, the timing of the gunshots supports Ross’s version of events. As the number one witness against Wagner, Julian sealed Wagner’s fate with his testimony. Julian would be tried shortly afterwards for burglary only, not as an accomplice to murder.

In the Nanaimo courthouse, the judge addressed the court and described his take on the events: Wagner entered the store armed with a pistol to commit burglary. He had that pistol to avoid apprehension, if it came to it, and had long prepared to shoot someone. The jury, apparently split until the final minutes, took four hours to come back with a guilty verdict. Wagner was condemned to death by hanging, with his execution set for August 28 of that year.

The case was murky and evidence scant, but the Flying Dutchman had a reputation. After the trial, in the same petition Wagner’s lawyer sent to Ottawa to request an appeal, he claimed some jurors had made up their minds to have Wagner executed before the court case began.

***

The Flying Dutchman’s final months were not without drama, both in his cell and on Vancouver Island. Days before the trial, the Island’s coal towns erupted in riots. Coal miners demanded better working conditions and threatened to unionize. The situation prompted the Provincial Police to call in the militia, who made mass arrests. The prisoner records for the Nanaimo Gaol at this time are choked with miners’ names.

Beginning the day after the trial, guards watched Wagner around the clock. This was called a death watch. Unlike at Walla Walla, he was assigned no labour, hard or otherwise. In the months leading up to the execution, Mrs. Wagner and the children visited nearly every week. On one visit he gave her $250 from the sale of the Spray. She also took his watch, chain, and other effects. The remaining $50 from the $300 boat sale he kept. As with the gaols in Victoria and New Westminster at the time, prisoners condemned to death could purchase and cook their own food. Wagner regularly bought eggs, butter, and bacon, which the guards delivered to him.

After a final visit from his wife and children, Wagner attempted suicide by banging his head against the radiator in the shower. After that, guards shackled his legs with a chain so short he could only shuffle his feet.

***

Arthur Ellis, the Dominion of Canada’s official executioner, had hanged hundreds. Ellis was only the latest of many forefathers to undertake this grim task. Untold numbers met their end by his kin, who had been executing people for over three hundred years. The night before his current task, Ellis stepped into Wagner’s cell. He placed two fingers on the prisoner’s wrist—a touch to measure a pulse by the man who would steal it.

Due to the miners’ strikes, the execution was closed to the public. In the early morning of August 28, 1913, a handful of police constables, a Salvation Army officer, and Ellis gathered in Nanaimo’s gaol courtyard. Silence filled the dewy air. The assembled men faced the wooden gallows, where a noose, rigid and still, hung from the top beam. At the platform’s crest, high above the witnesses, the executioner grasped a black sack and leather straps. A door to the courtyard flew open. The Flying Dutchman stumbled into the sunlight.

The hanging began at 7:45 a.m. in the gaol’s courtyard. According to a first-hand account of the execution published in Outlaws and Lawmen of Western Canada, the conditions were right for Ellis to attempt a world record for the fastest hanging. Ellis had noted that the distance between the courtyard door and the gallows in Nanaimo matched the location in England where the current record was set by his uncle. He left the bottom of the gallows unscreened so the timekeeper could see the moment the condemned man’s toes hit the gravel.

***

When Wagner stumbles into the courtyard, those gathered lift their hats, not out of respect for the convicted murderer but because it is the law. As soon as Wagner reaches the trap on the gallows, Ellis yanks the sack over his head, pinions his legs with the strap, and jerks the noose tight behind his ears. Before the Salvation Army officer can say four words of the Lord’s Prayer, Ellis springs the trap. The Flying Dutchman’s third vertebra snaps, his toes graze the gravel below the scaffolding, and he meets Death instantly.

Ellis thrusts his hand into the air. “Time!”

***

Published versions of this story have invariably painted the Flying Dutchman as a cold-hearted desperado and the police as heroes. This is a common narrative in any story where a police officer is murdered, but truth is rarely so cut and dried. The BC Provincial Police both protected and acted against the public. According to volume three of British Columbia: From the Past Times to the Present, a biographical account of prominent community members, Chief Constable David Stephenson was respected and generally considered a fair officer. Conversely, a common photo of Stephenson shows him leading a gang of mounted constables, ready to quell the strikes in Nanaimo.

In the case of the Flying Dutchman, Stephenson managed to stop the crime spree, but one of his officers paid for the victory with his life. What Stephenson thought of the justice Wagner received, we don’t know. Other problems were likely at the forefront of his mind. The strikes continued, only abating during the First World War. In 1916, Stephenson retired at his own request after thirty-six years on duty. After the war ended, the strikes worsened.

Other BC Provincial Police constables were indistinguishable from the criminals they arrested. Not long after the Flying Dutchman was hanged, William Julian pled guilty to breaking into the Fraser and Bishop General Store and served a five-year sentence. Shortly after his release, police scoured the coast for two pirates who were robbing communities in the same manner Wagner and Julian had. Police caught up to Julian on February 18, 1920, and arrested him. The next day they arrested his accomplice: George Hannay, the officer who had arrested Julian on Lasqueti Island in 1913.

Excerpted from A Place Called Cumberland by Cumberland Museum & Archives. Edited by Rhonda Bailey. Copyright © 2024 by Cumberland Museum & Archives. Essay by Dave Flawse. Excerpted with permission from Figure 1 Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Sources

All sources can be found in A Place Called Cumberland where this story appears.